I watched female students in our school struggle to take center stage, and I thought long and hard about power and how uneasily it is granted to women. In the early days at the, I was often quizzed about why my choice of repertoire had a “feminist agenda,” when I knew full well that if I did a season of Mamet and Shakespeare, no one would ever accuse me of having a male agenda. I would have to prove that, again and again. I realized then that I could never take for granted that it would be assumed I knew what I was doing. His behavior was never questioned I was simply supposed to be a good girl, accept the authority of the great man, and support his wishes.

I remember Berkoff asking me in extremely patronizing tones whether I would like to warm up the cast before he began work. When Berkoff himself arrived on the scene two weeks into rehearsal, after I had cast, designed, and prepared the entire production, I was suddenly relegated to driver and junior acting coach, while the great man took over and directed his play. One of my first experiences as a young director came back to haunt me: When I returned from England to the United States in 1981, I brought back a pile of plays I wanted to direct, including Steven Berkoff’s classically inspired Greek, which I managed to persuade LA Theatre Works to let me stage.

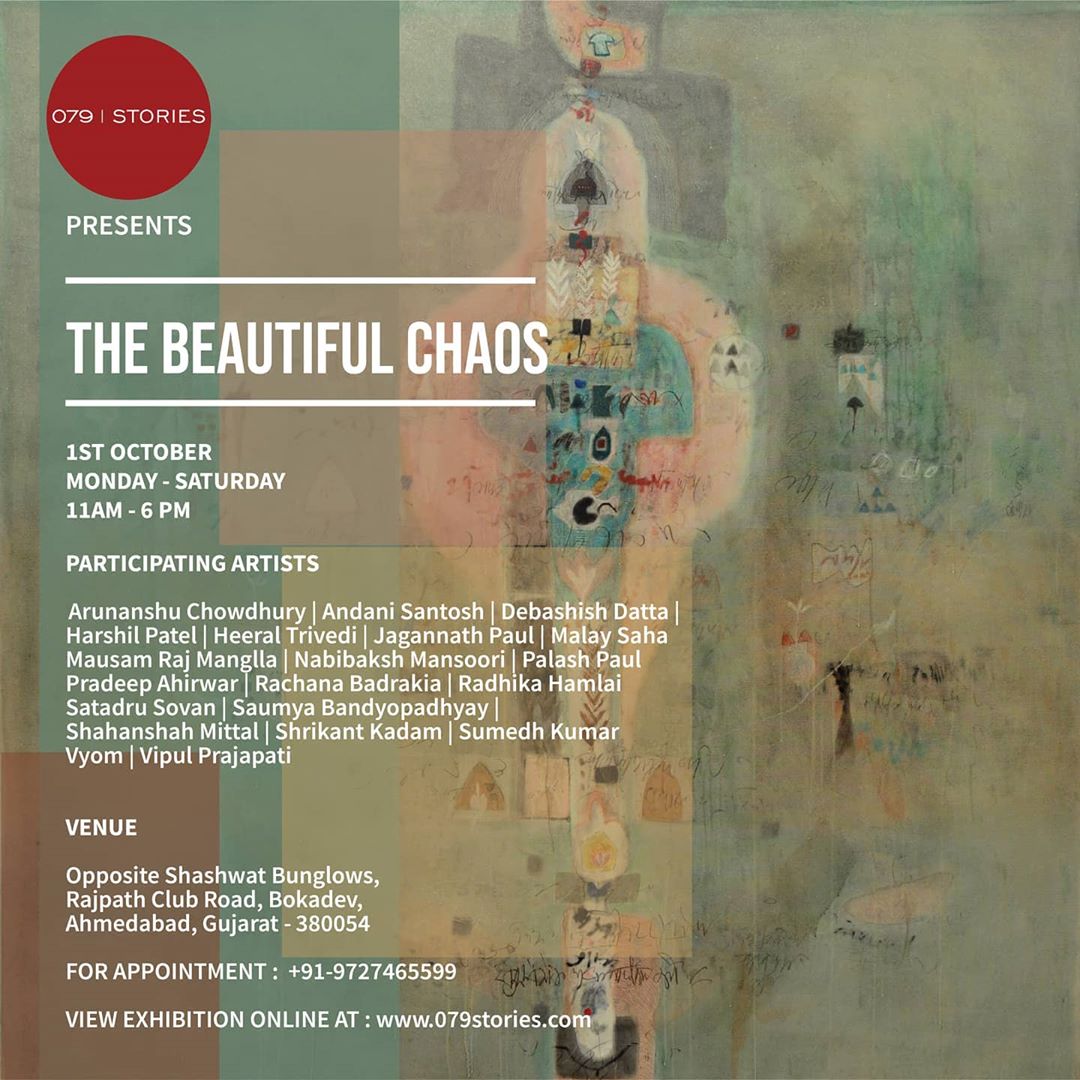

The juggling act required of female artists in the theater, particularly those in positions of authority, is acute, and our failures are often seen as failures of our entire gender. Yet it was only in the process of writing this book that I began to realize how long it actually took me to stop playing at being a man and to acknowledge my own personal point of view on the world and on the work. Much has been written about the paucity of female voices in the contemporary theater, and about how rarely stories by and about women dominate. The following is an excerpt from Carey Perloff’s memoir “Beautiful Chaos: A Life in the Theater.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)